Although there are many record producers doing excellent work, there are few of those iconic producers that achieve a result that inevitably gets labeled as “their sound”. These are the “personality producers” – men who produce in such a unique way and with a distinct style that the sound becomes there own. This article examines three such producers to give you a run down of how they craft the hits.

Phil Spector

Phil Spector is often regarded as the very first personality producer. His “Wall of Sound” was a result of grand production styles, which were completely unheard of in the era in which he worked – the early Sixties. Using the most primitive of recording equipment (by today’s standards) – a twelve-channel mixing console, and a four-track tape machine, Spector’s sound was immense. Additionally, these recordings were all deliberately done in mono, not stereo.

Phil Spector is often regarded as the very first personality producer. His “Wall of Sound” was a result of grand production styles, which were completely unheard of in the era in which he worked – the early Sixties. Using the most primitive of recording equipment (by today’s standards) – a twelve-channel mixing console, and a four-track tape machine, Spector’s sound was immense. Additionally, these recordings were all deliberately done in mono, not stereo.

The “Wall of Sound” was achieved through the use of natural acoustics and by recording many musicians at the same time without any form of acoustic isolation. The lack of acoustic isolation and by cramming as many musicians as possible into a small space was all part of the finished result. Spector mainly worked out of Gold Star studios, a small recording space which had a ceiling height of 14’ (4.2m). The studio dimensions made the sound bounce all over the room, and also produced room resonances, which then amplified certain instruments at certain frequencies. Guitar chords that were fretted needed to be boosted more at the console, which in turn boosted any spill coming from the drums.

Spector would often multiply the number of instruments to achieve the massive productions that he had in his head. When recording “River Deep, Mountain High” for Ike and Tina Turner, there were no less than four bass players. Over time Spector began piling in more musicians simultaneously into the studio – 3 pianos, 5 guitars, and even three drummers.

And the amazing productions were made even more remarkable by the fact they were in a studio that had no equalisers, compressors and only a maximum of 12 microphones.

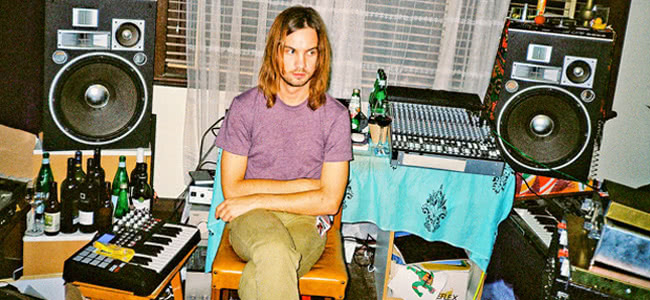

Kevin Parker – Tame Impala

Kevin Parker from Tame Impala is living proof that in order to make a great record, you don’t need great gear, a great studio or even have much of an inkling of engineering/production at all. In fact, it is the distinct lack of gear and associated technical skills that produce the Tame Impala sound.

Kevin Parker from Tame Impala is living proof that in order to make a great record, you don’t need great gear, a great studio or even have much of an inkling of engineering/production at all. In fact, it is the distinct lack of gear and associated technical skills that produce the Tame Impala sound.

Parker is the ultimate home studio hacker. Most of his production style is based on trial and error, and the fact that he has no formal training in engineering or production gives him freedom to try things that professional engineers would actively discourage. The fact that he is “doing it wrong” by usual standards, produces a sound that is distinctly unique and personal. To say his approach is “lo-fi” is an understatement, considering the 2013 Lonerism album was produced in his bedroom in Perth with microphones plugged directly into his laptop, using make-shift cables held together by sticky tape. You get a sense of a total disregard to rules and conventions of audio engineering. Ironically, Parker’s “engineering skills” earned him an ARIA nomination for Engineer of the Year in 2013.

Interestingly, drums are where he spends most of his time. Again, going against convention he records drums as one of the last instruments on any given song, using only three microphones instead of the usual 12 or more used in modern recordings. His limited microphone choice also produces the unique drum sound. Although he uses a conventional Shure SM57 on the snare, he also has a 57 for the kick – a very unusual choice. His third drum microphone is a Rode K2, which is used for the drum overhead.

Heavy compression is part of the Tame Impala drum sound, using a selection of vintage compressors. Vocals are recorded with a handheld dynamic microphone and drowned in lots of vintage echo.

When mixing, Parker will employ the services of an external engineer – for Lonerism it was David Fridmann. But mixing also requires experimentation rather than making things just listenable. Flanging the entire mix, or adding a wild vocal delay that repeats itself all the way through the track are again, not the universally accepted way of doing things, but nevertheless give Tame Impala that unique sound.

Trent Reznor And Nine Inch Nails

Trent Reznor has cut through new boundaries in terms of sonics and production with the recordings of Nine Inch Nails. His work with producer/engineer Alan Moulder, and the album The Fragile (2000) was particularly unique. The huge palate of abrasive sounds created for the album is a product of hours and hours of painstaking work resulting in textures that cannot be simply achieved with the use of a plug in and some vintage synths.

Trent Reznor has cut through new boundaries in terms of sonics and production with the recordings of Nine Inch Nails. His work with producer/engineer Alan Moulder, and the album The Fragile (2000) was particularly unique. The huge palate of abrasive sounds created for the album is a product of hours and hours of painstaking work resulting in textures that cannot be simply achieved with the use of a plug in and some vintage synths.

Reznor’s production style is one of fluidity. Songs evolve during the process of recording them rather than treating the writing and recording as separate processes. Reznor uses the studio as an integral part of the actual composition process.

When recording The Fragile at Reznor’s Nothing Studios, Moulder noted that they would work together for 2-3 days on any one song and it was a case of “anything goes”. There were just a template of ideas, and they often start with a guitar, just plugging in to anything “that took our fancy”. From there they might move on to drums or bass or keyboards, whatever inspired them at the time. By evolving songs in this way and not in any set, logical order, it ensured that sounds would be inconsistent from one song to the other. No drum sound was intended for the whole album. Drum sounds were recorded quickly, taking only 20-25 minutes to get a starting sound, then they were ready to record.

As part of this fluid production process, mixing would also occur as the song evolved. It would then become apparent that additional layers needed to be added in certain sections, or that instruments needed to be re-recorded. The songs were also continually being arranged, cutting and pasting on Pro Tools or even grabbing sounds from one song, and pasting them into another completely different song. A song called “La Mer” for example started out as a solo piano, but then drums were added from a completely different song, and dropped in to fit the tempo. Different guitar loops were added from other Pro Tools sessions. A subsequent decision to remix the song eventually resulted in it becoming yet a completely new track with different drum sounds, drum pattern, but identical chords and tempo. This song became “Into The Void”.

There was a deliberate attempt to make sounds “gratuitously unusual” in order to stray away from convention. Experimentation was the norm in the recording process. In recording drums for example, Moulder tuned them very low and very badly. These drums then triggered a synthesiser which was then fed to a PA system. The PA/synth sounds were mixed in with the natural drum sounds to create a unique sonic element. These were not meant for any song in particular but appear as different textures right across the record.

Getting your name out as a “personality producer” requires you to take different approaches and stray away from normal conventions. Once you’ve learned the rules, it’s OK to break them!

Jason de Wilde is a senior audio professional and heads the audio department of AIM, if you’re interested in exploring more about audio engineering visit www.aim.edu.au