Back in May, Tame Impala frontman Kevin Parker dropped a bombshell during a Reddit AMA. Despite fronting and writing the majority of the music for one the biggest bands to come out of Australia in recent years, Parker revealed that he’s made no money from the band’s overseas sales.

“Up until recently, from all of Tame Impala’s record sales outside of Australia I had received…. zero dollars,” Parker told fans. “Someone high up spent the money before it got to me. I may never get that money,” he added.

According to Parker, his main revenue stream has been selling Tame Impala’s music to brands like Blackberry. The revelation came as a shock to many fans and especially musicians – if a band the size of Tame Impala isn’t making money, what hope do I have?

What hope, indeed? Following Parker’s comments, reports arose that Tame Impala’s former label, Modular Recordings, were at the centre of an increasingly convoluted tangle of litigation. As Tone Deaf reported, German publishing giant BMG were suing Modular and its partners over Tame Impala’s overseas royalties.

Modular’s co-owners, Universal Music Australia, part of the giant Universal Music Group, quickly responded, saying Modular chief Stephen Pavlovic was the one responsible for paying out royalties. Pavlovic claimed there was a misunderstanding over the contract agreed to by UMG, Modular, and himself.

Meanwhile, Tame Impala weren’t receiving any money for overseas sales of their first two albums. According to Williard Ahdritz, CEO of publishing house Kobalt Music, they’re not the only ones who aren’t getting what they deserve and the problem, he argues, is systemic.

“Why should music, which is beloved by people in every culture, across every language and corner of the globe, be anything less than an economic powerhouse?” he writes. According to a new op-ed in Digital Music News, consumers and artists should be enjoying a new “golden age of music”.

“Simply put, the back-end pipes of the music industry are broken.”“Today, live ticket sales have hit an all-time high. Music publishing values and revenues have increased. Tech companies are investing in music by the billions. And, perhaps most importantly, more people have legitimate access and choice, in both platforms and music, than ever before.”

“And for music creators, one global hit can unlock millions of revenue streams from billions of transactions and micro-payments that add up to more demand and music usage than ever before.” The problem? The same one the music industry has always had – technology.

“Yesterday’s antiquated infrastructure, which much of the industry still employs, was not built to handle the enormous volume and complexity of data that digital music requires today.” In the same way the industry was slow to adapt to the digital revolution, today’s music industry bureaucracy simply can’t handle the digital age.

What’s perhaps most disturbing is just how clogged-up and convoluted the system is. “One hit song today can generate up to 900,000 distinct royalty payments, and just one of those could be from Spotify in the U.S., for billions of individual streams, that then have to be accounted for and paid out to each of the song’s different writers,” says Ahdritz.

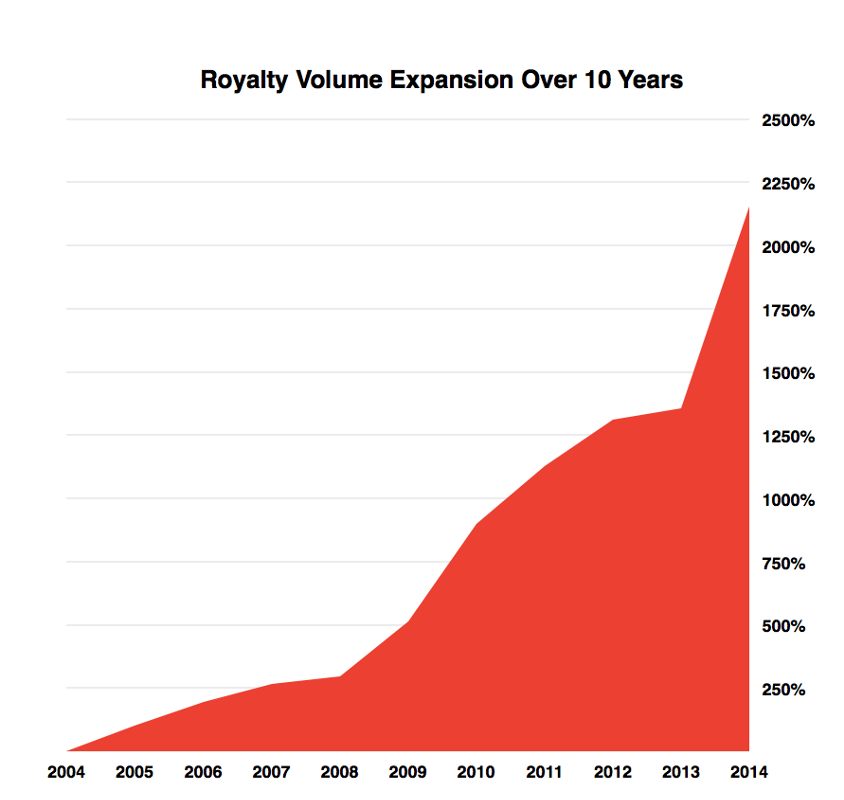

Image via Digital Music News

“Over 75% of those 900,000 royalty lines come from streaming services (i.e. YouTube, Spotify, Pandora, Tidal, Rdio, etc.), each delivering data in different ways, for different time periods, using different calculations, across different geographies.”

“Since 2004, this volume of royalty lines has grown by almost 2,500%. And with the announcement of Apple Music last week, plus Spotify’s bullish determination to grow, and the number of new services jumping into the game, the volumes of data to come from streaming will be staggering.”

“It’s no surprise then that the music industry’s outdated back-end accounting systems are not capable of processing all of this complex data in an efficient or timely way. Simply put, the back-end pipes of the music industry are broken.”

According to Ahdritz, this is something that goes unsaid in the background, until “a major talent pulls their catalogue from a streaming service in protest” or, say, reveals it nonchalantly to some fans during an AMA session on Reddit.

Basically, musicians have the odds stacked against them. Unless you’re exceedingly savvy and business-minded or can afford a good business team to have your back, you’re up against a monolithic bureaucracy that’s fairly confident you won’t be auditing them any time soon.

[include_post id=”446013″]

“Remember, this is a songwriters’ salary we are talking about. And not just the superstars, but thousands of writers you’ve never heard of creating your favourite songs,” says Ahdritz and though the picture he paints is grim, he reckons there’s still hope.

“In addition to the work we’re doing at Kobalt, there are several technology-focused companies working to better serve music creators. Apple’s acquisition of MusicMetric and Spotify’s purchase of Echo Nest are both signs of the companies’ support for cleaner and deeper data delivery to licensors and artists.”

“All of this is music to my ears, signaling a shift toward an industry that embraces a higher standard of respect for the rights of artists and songwriters, as well as a real commitment to technology as an opportunity, rather than an obligation.”

Frankly, this shift can’t come soon enough. As Ahdritz notes, “every player in the music industry must commit to work with technology, not against it” because that is the true “future of music”.